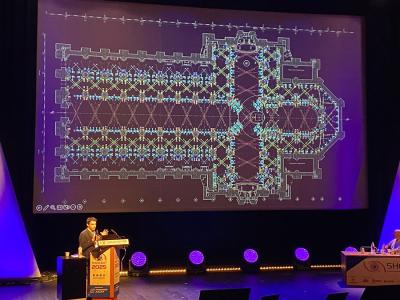

Italian lighting designer and architect Marco Migioli of ArchiLight Studio presented at Showlight 2025 on how illumination changes everything. This may seem like an obvious statement, but the examples he chose illustrate the critical nature of lighting design. How it can expose details hidden for centuries and celebrate forgotten craftsmanship. How lighting choices can take a location from welcoming to threatening, and provoke emotion from fear to awe.

During his session, Miglioli discussed three recent projects that he had worked on. Raphael Sanzio's "Cross of Procession with Franciscan Saints" which was recently relocated to a new case in the Poldi Pezzoli Museum. The painted wooden cross was produced around 1500 and therefore required environmental and security protection, in addition to lighting in a way which would allow visitors to see the details in each of the miniatures, in the wood, and from all sides. Miglioli was awarded a LIT Lighting Design Award for this project in 2024, and you can read about his work shaping the light spectrum to support the beautiful colors and detail in the cross without subduing the warm tones of the gold.

The Shoah Memorial, Track 21, inside Milan's Central Station, is the only Holocaust memorial to the deportation of Jews and other people persecuted by the Nazis that is in a train station which has not been redeveloped to obscure its past. Deportees were taken from San Vittore Prison and loaded onto livestock cars there before being taken to death camps. The entrance is lit by sunlight through glass, but as the visitor moves deeper into the museum, Miglioli takes them into darker spaces, lit by LEDs blended to evoke the sodium lighting of the period, while they experience the real-life vibrations and sounds from working trains in the station above. The transition from light to gloom, and the proximity to real trains, helps the visitor to reflect both on the people who made those final journeys from Italy and the indifference of the neighbors and fellow citizens who allowed it to happen. For more information on this award-winning project, click here.

Live Design caught up with Miglioli at Showlight to talk to him about his training as an architect, why there is such drama in his work, and the the third project in his presentation, relighting the iconic cathedral in Milan.

Live Design: You trained as an architect in Switzerland but work as a lighting designer. What is behind those choices?

Marco Miglioli: I chose to study in Switzerland because, while it is a rigorous program with longer hours than in Milan, it also had more artistic classes, such as the history of cinematography and scenography classes.

I came to lighting by chance – we had only one tiny course about lighting, just on [commercial or residential] lighting in a space, but I wanted to learn more about scenography as a part of architecture. I went to La Scala to learn more and there I met Marco Filibeck. [Filibeck is a leading figure on the Italian and international lighting scene.] He suggested I join him and help on Madama Butterfly in Turin. I said, "Why not?"

From that moment I realized that lighting was my career. Light is for transmitting emotion and creating space. I worked a couple of years in stage lighting and then went back to architectural lighting. But my real training is for the stage where I worked and learned from many companies.

I try to bring theatrical points into architecture – lighting is not just to stop people falling down the stairs but to reshape a space and add something more, some emotion.

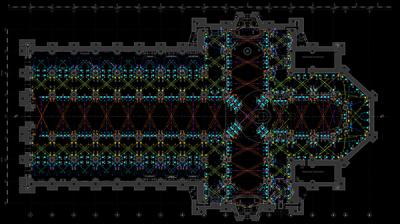

Click To Expand The Light Plot

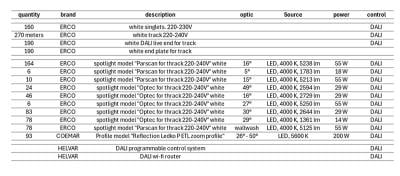

LD: For the project at the Duomo, I believe you worked with Ferrara Palladino Lightscape as lighting designer and the lighting won a Legambiente Award for environmentally friendly innovation.

MM: Yes, in terms of energy use, we reduced by two-thirds of the previous system because that was based on powerful discharge lamps which were all simply on/off. We also increased the total output of the lighting by 30%, even though we were saving electricity.

LD: Building of the Duomo was started in 1386 with updates and additions for the next 600 years. How did this evolution of building and styles impact your work?

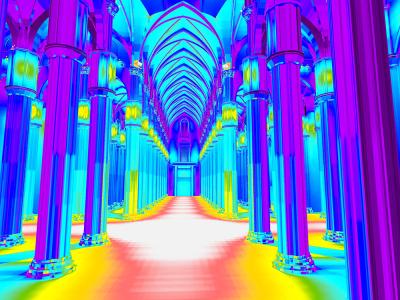

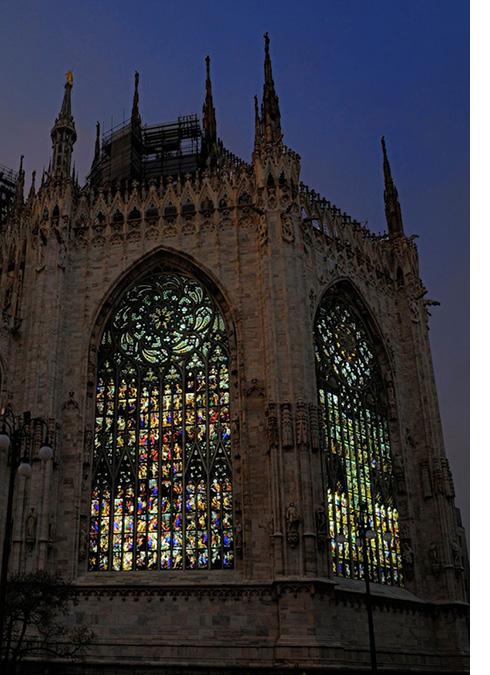

MM: Gothic cathedrals symbolize light, but in Milan, the atmosphere was dark and almost oppressive. The vertical surfaces and statues were lost in shadow, and looking up, the glare from the discharge lamps made it impossible to see the ceiling. The new design reveals the richness of the cathedral and highlights the vertical thrust of the gothic architecture.

To avoid drilling into the marble and damaging the historic building, we used the old holes for previous lighting systems. Our goal was to highlight the capitals on the columns and show off friezes and details of sculptures that are high up, so we needed fixtures close to them rather than relying on powerful beams below. But because each of the pillars and capitals were hand cut centuries ago, they vary in shape and alignment so we could not create a one size fits all solution.

We developed a self locking mount for adjustable brackets designed to work around the structures irregular geometry. Instead of 100 different discs to wrap around each column, we designed a self-locking and adaptable mount that would work with each one, a semicircle that locks together or can open up, and brackets that adapt to the irregular geometry. The mounts allow very precise focus too, to capture the texture and relief of the carvings.

LD: What were some of the challenges?

MM: The cathedral had to remain open the whole time. To accommodate that, we planned for small, localized mobile zones that were easy to move when needed. Scaffolding was not an option because of damage to the stonework so we used raised platforms, and despite my fear of heights, I became certified for working at height.

Unlike in a theatre where lights can be adjusted later, the scale made that impossible once we had left the area and also I did not want to climb up there again! The cathedral's complicated geometry made aligning the fixtures difficult, and also we could not turn off the lights to focus. Instead we had to number and aim each fixture in advance of mounting it based on 3D models of the building.

In addition to the pillars and capitals, we focused on the windows, which by day project colors from the stained glass on the marble, and by night make the cathedral glow from the inside.

LD: How is the lighting controlled?

MM: Each fixture was placed to support different lighting scenes and is controlled by a tablet. The control system relies on Wi-Fi with repeaters placed along corridors that run alongside the nave. Like music, light is a language shifting in intensity and tone and creating atmospheres. We can now adjust for mass or bring it all up for civic events such as operas, but all lighting features were designed to avoid flicker for broadcast events.

If, in the future, the cathedral requires a change in lighting, the supports will stay there and the fixtures can be updated without resetting electrical cables. The controls rely on a Wi-Fi system and all the cables are out of the way but running alongside the nave so they can be updated even while people are there.

LD: What was your favorite part of this project?

MM: The construction part, climbing up to the capitals even though I am scared of heights. I still remember the first time they lifted me 30 meters off the ground. I prefer to work onsite and there is satisfaction in seeing the effects as I work. I like to touch the light and move the fixtures.